We strive to protect and manage our local resources in a respectful and responsible manner.

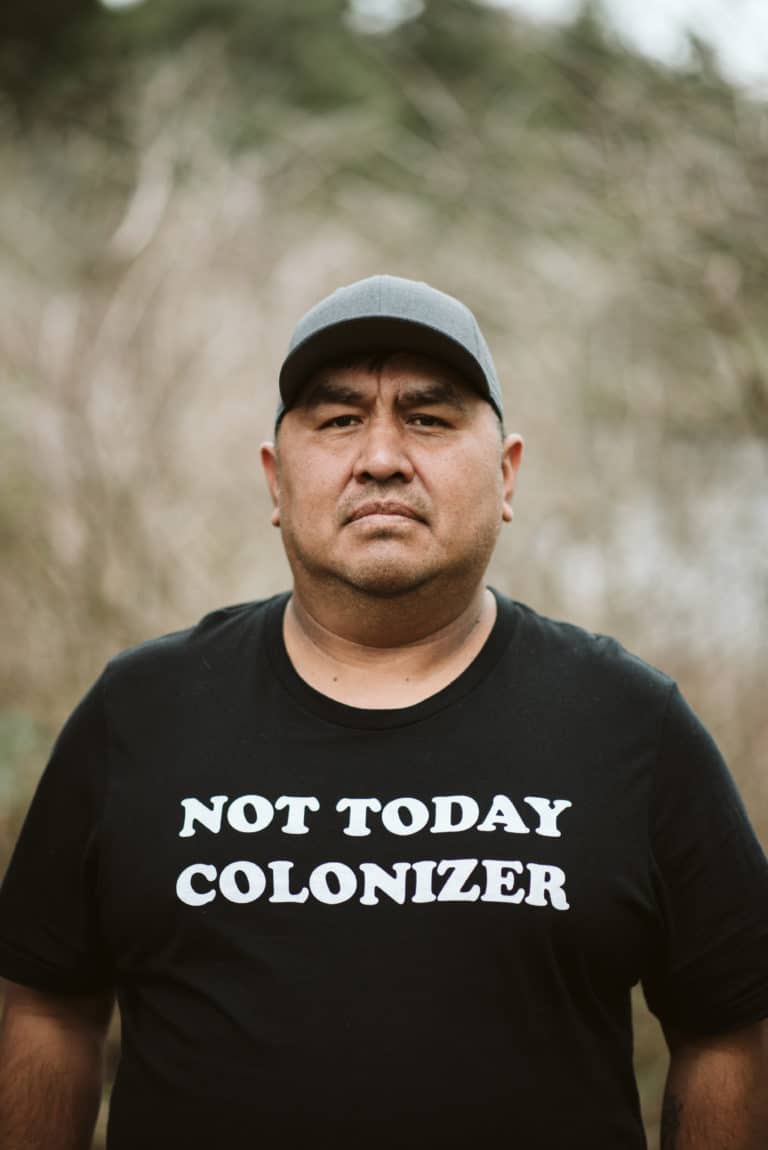

We are a strong people, with a rich history and bright future. Join us in celebrating our Nations.

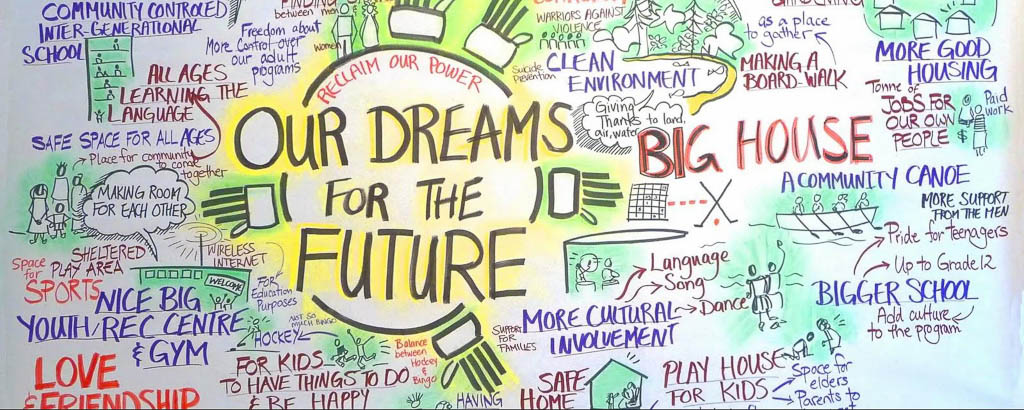

Our Nations’ future is bright. Discover the goals and priorities of the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations.

Excerpted from “Tsulquate: The Demographic Story” (1984):

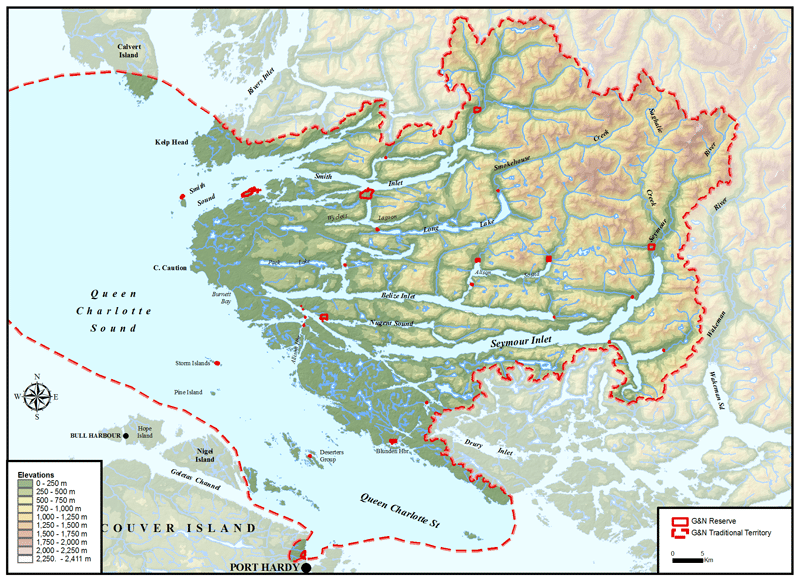

Prior to the beginning of on-going contact with Europeans in the nineteenth century the ‘Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala, like others on the coast, lived by harvesting sea and land resources and were socially, politically, economically and culturally involved with other bands in the region through trade in goods and labour, inter-marriage and involvement in potlatches. Again like other coastal and interior bands, the ‘Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala participated as trappers in the European fur trade which began in earnest in this region during the mid-nineteenth century.

In Bella Bella to the north, the Hudsons Bay Company established Fort McLoughlin in 1843 and it was to this fort that the ‘Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala first traveled to exchange furs for European goods. (Holm, 1983) Following the discovery of coal on Northern Vancouver Island, to the south of ‘Nakwaxda’xw/Gwa’sala territory, the Hudsons Bay Company established a second fort – Fort Rupert – near what is now the town of Port Hardy. Several First Nations in the area moved to the new fort and the ‘Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala also began to centre their trading activity there. However, due in part to their relatively isolated geographic location, the ‘Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala involvement in the fur trade was peripheral compared to that of their neighbours to the north and to the south. Isolation, however, did not protect the ‘Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala from the onslaught of a series of epidemics of contagious diseases brought by the Europeans and against which the First Nations population had no immunity.

Beginning in 1862 with a smallpox epidemic which alone is estimated to have wiped out 1/3 of the First Nation population of British Columbia, subsequent epidemics of measles, pneumonia, tuberculosis and influenza continued to take their toll through the 1920s. Poor health among the First Nations population was further exacerbated by confinement to frequently overcrowded reserves, changes in diet, lack of medical care and attention, the introduction of liquor, and the crowding together of children from all over the coast in residential schools. Research has shown that such massive declines in population immediately following the arrival of the Europeans has been the experience of Indigenous peoples throughout North, Central and South America as well as Oceania and Africa.

By the late nineteenth century the market for furs in Europe was declining and the fur trade era on the northwest coast was coming to a close while permanent European settlement was beginning in earnest [sic]. During the 1880-1900 period an Anglican missionary, Reverend A.J. Hall, established missions in both Fort Rupert and Alert Bay and opened a school for First Nations children in Alert Bay. Two entrepreneurs, Spencer and Hudson, opened a fish saltery in Alert Bay and the Nimpkish Nation was persuaded to move from their traditional home at the mouth of the Nimpkish River to Alert Bay in order to work in the saltery. Logging camps and fish canneries began to spring up all over the coast and pressure from both missionaries and employers began to be applied to the provincial and federal governments to prohibit potlatching which was seen by both employers and missionaries as a detriment to the spiritual, moral and economic development of the First Nations people of the region.

The period 1900-1920 saw development proceeding along these same lines with Alert Bay quickly becoming the administrative, economic, religious and educational centre of the region. The first St. George’s Hospital was built in Alert Bay in 1909.

While the ‘Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala peoples continued to live in the more remote region of Seymour and Smiths Inlets and were less involved on a day-to-day basis with the new settlers and political and religious authorities than were the Kwawkewlth [Kwakiutl] who lived in closer proximity to the centres of Alert Bay, Campbell River, and, now, Victoria, their isolation was by no means complete. St. Michael’s Residential School, a large institution to which most Indigenous children in the region were taken at around the age of six from the 1920s through to the 1970s, was built in Alert Bay in 1929. ‘Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala children are noted as having been in attendance there on 1929 and subsequent census. Adult members of the ‘Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala Nations worked in the new commercial fishing, logging and fish canning industries now beginning to locate in and around their home territory.

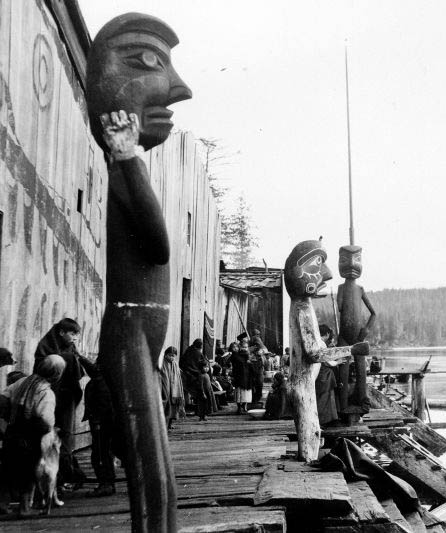

Their relative isolation was, however, significant in a number of ways. Bill Holm, in his book “Smoky Top: The Art and Times of Willie Seaweed”, notes that the ‘Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala remained more “culturally conservative” – meaning that First Nations religious beliefs, art, ritual and social organization persisted for a longer period of time than their neighbours. Isolation also meant less access to what few educational and employment opportunities existed and to medical care and treatment.

The 1930s were the years of the Great Depression throughout the western world and the fishing industry, like most others, slowed during these years, bringing hardship to the entire region. During the years 1932-1943 the [Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw] population began to stabilize in size and 1944 marked the beginning of their recovery from the initial onslaught of European settlement.

In the post World War II era (after 1945), Canada entered a period of liberalism and social welfare programs and health care services began to expand and became available to larger and larger portions of the Canadian population as a whole and to First Indigenous people in particular. Following the defeat of Hitler and the revelation of Nazi atrocities, Canada’s image of itself both nationally and internationally as a free and democratic nation where all citizens are equal regardless of race became increasingly marred by the existence within Canada’s borders of a group of people who were legally, politically, economically and socially differentiated Indigenous from non-Indigenous Canadians became more glaringly obvious and more socially unacceptable. Programs designed to better the material conditions on reserves, to improve health standards and to assimilate the Indigenous population began to be implemented on a larger scale than previously.

Since the end of World War II, and particularly during the 1960s, the Canadian federal government stepped up its activities in the field of Indigenous administration and various “solutions” were being investigated. Since the objective of government policy was to assimilate Indigenous peoples into the mainstream of Canadian society and to eliminate any special status for Indigenous peoples as quickly as possible and within budgetary constraints, geographic isolation was seen as a serious impediment to this goal. It was in this context that the amalgamation of small Nations into larger units and the relocation of geographically isolated Nations to urban and semi-urban locations was encouraged and implemented throughout Canada by the D.I.A.N.D. [Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development].

The following is excerpted from “Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw Stories” (1997):

About 50 years ago the Canadian government decided that the ’Nakwaxda’xw people in Blunden Harbour and the Gwa’sala people in Takush were not living in very good places. Actually the Gwa’sala people agreed. They wanted to move to another place in Smith Inlet with better water, a better place for houses, near a store and a cannery where they worked. But the government officials had a different idea. They wanted the people to move close to a town like Alert Bay or Port Hardy. It would cost less to pay for education for the children there, and for medical help, and they hoped that the First Nations would become like white people, if they lived near them.

If you want people to do something, you have two ways of making them listen. You can threaten bad results if they don’t do it, or you can promise them something good if they do. The Canadian government used both methods to make the ’Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala people move to Port Hardy. They said that the government would no longer help the people build good houses and have school and medical help, if they stayed where they were, but the government would supply everything the people needed, if they moved. There would be new houses, a community hall, a place to moor the fishing boats, good jobs, a good school in Port Hardy, and so on.

For about ten years the government kept making these threats and promises. Finally the people gave in and agreed to move. But then the government suddenly said, “We don’t have enough money right now to keep all these promises. A few people should move. The rest can come later.” But that was impossible. How can you leave an auntie behind, or a grandfather, or your sister and her baby?

So in 1964, after the fishing season was over, almost all the people moved to the Tsulquate reserve. The Tsulquate reserve was not meant to have a whole village of houses built on it. It was just a campground the Kwakiutl people from Fort Rupert used when they wanted to dig clams. Even today you can see how hard it is to build houses here. Big rocks are in the way, and the road is steep in places. When the people came from Takush and Blunden Harbour, just three small houses were built for them in the flat part of the reserve near the bridge, and even those weren’t finished. They didn’t have water or toilets. There wasn’t a good place to moor their boats. People had to leave them in the Tsulquate River. You can see how even today it is hard to keep the boats from breaking or sinking in the River. The people in town and the children in the schools were strangers, most of them not at all friendly. And if you felt terrible about how you had to leave, liquor was easy to get. Then you could forget your troubles for a while.

All of us have heard stories about that terrible time from our relatives who lived here then. Most of those people don’t really want to talk about it because it was so bad. Six years after the move, the government investigated what had been promised and what had actually been done. The government workers doing the investigation decided that the government had handled everything badly and had not kept its promises. Another government worker wrote a book about the village. He called the book “How a People Die”, because he didn’t believe that the ’Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala people would last through this terrible time.

When he wrote his book, there were about 200 ’Nakwaxda’xw and Gwa’sala people living in our village and nearby… [Now] we build our own houses, run our school, medical clinic… and invest in fishing and forestry. Nation members study at colleges and universities to become teachers, lawyers, policemen, accountants, managers. Others operate seiners and gillnetters, or are loggers. Some are painters and carvers. Some are learning how to look after the forest and the rivers so that there will always be trees and fish. Families hold potlatches and young people are learning to dance and sing, learning their names, so that they can potlatch when their time comes. And now the government of Canada and the government of B.C. have finally agreed with the First Nations living here that things went wrong when the white people came… If we wrote that book about our village now, it would be better to call it “How a People Live”.

We will be a community with a strong and distinct culture, where our language, traditions, and the teachings of our ancestors live on throughout the generations. We will continue to be care takers of our sacred and important places. We will gather often to celebrate and support each other.

We will be educated, hard-working and responsible, making sure that we provide for ourselves and our children. We will cherish our traditional home lands, making sure that we care for the natural world so that it can continue to care for us.

We will have strong leaders who are accountable to their people. We will look after one another and strive for good health on all levels, physical, mental, emotional and spiritual. We will build strong families and respect ourselves and those around us. We will show this respect by taking care of our community.

We will be strong and independent, but we will also be connected to other communities across the globe, working together to achieve common goals. We will exist forever as the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw people, building on the legacy left to us by our ancestors and moving towards a bright future.

Chief

Councillor

Councillor

Councillor

Band Manager

Councillor

Councillor

Councillor

Councillor

Councillor